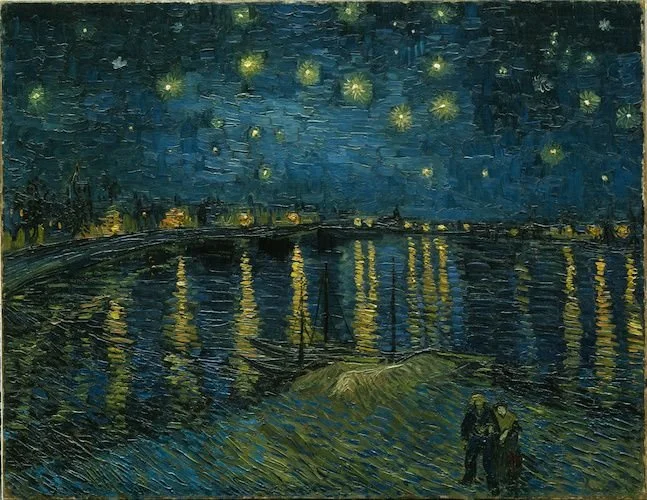

The Starry Night (1888) by Vincent van Gogh. Courtesy of Musée d'Orsay. Via Van Gogh Worldwide.

William Hazlitt was one of England’s greatest art critics, second only to Ruskin. He was also a theatre critic and he has been credited with reviving interest in Shakespeare. A contemporary of the Romantic poets, Hazlitt knew Wordsworth and Coleridge, and he was good friends with Keats. While not strictly considered a Romantic himself, Hazlitt was a product of his time. The Romantics lived through a turbulent period where technological advances were changing labour conditions and reshaping the countryside with railways and “dark Satanic mills”. As a reaction, they turned to nature and looked inward to human nature.

Hazlitt had a mixed reaction towards technological advancements. It’s difficult to imagine today, but the invention of the steam-powered printing press (introduced by The Times in 1814) had a similar effect on the public imagination as internet blogs, forums and AI generated content do today. While the steam-press undoubtedly democratised knowledge, Hazlitt feared that it would lead to a culture of “talkers, not doers”¹ and that this would lead to a shallow and superficial public mind – terms instantly recognisable in today’s debates around social media and AI use. He worried that the giddy pace of development and information would leave people stunned. At the same time, Hazlitt was complicit in the change as he became a journalist publishing regular reviews, eventually becoming credited as the greatest essayist in the English language². Some have even gone as far as labelling him the first blogger³.

Ultimately, Hazlitt was not too concerned with technology’s impact on art, which he felt was supremely “singular”. He wrote that the arts differ from the sciences in that they are not “cumulative”. As Paul Hamilton explains, for Hazlitt “The arts do not get better, in the sense that Shakespeare can be said to write greater plays than Sophocles. Nor do they grow obsolete, in the sense that Ptolemaic science has been superseded by Newtonian physics”⁴. So while Einstein builds on, and improves upon, Newton, it is not possible to aggregate Leonardo and Van Gogh – a blend of their best bits would likely just be a mess.

Hazlitt developed a new aesthetic category that he termed “gusto” to describe a kind

of “X-factor” in art.

While many paintings accurately depict their subject, only great paintings have gusto, or the ability to describe the essence or character of their subject – something machines (including AI), or even most humans, cannot replicate. To put it another way, true artists not only depict what something looks like, but also how something feels, or at least how the artist feels about it. Hazlitt was writing about figurative art but, with some adaption, his concept of gusto is equally applicable to abstraction or conceptual art which also describe feelings about experiences, in a way.

I have described elsewhere how “gusto is necessarily particular to each artist. It comes in different varieties, because each artist has their own strengths and those who manage to achieve a sense of gusto will do so in different ways”⁵. Consequently, if art is taught or reduced to a set of rules it will not only lack originality, but also gusto. This is why algorithmically generated art will always lack the “X-factor” – the subjective interpretation of a universal concept or experience.

So what, if anything, Can we learn from Hazlitt’s reflections on the “giddy” pace of technological change in the Romantic period? Despite William Morris’s later concerns about the loss of arts and crafts to mechanised production of artefacts, I think that most would agree that Hazlitt was correct to declare art as a human endeavour, and one that machines cannot replicate or replace.

As an early adopter of AI image generation (I was a Beta tester for Dall-E) I can attest to its limitations. While AI can be trained to mimic certain styles, it struggles with originality and (even more so) with consistency. While both can be achieved, this comes at great human effort – meaning that AI is in no place to replace artists (just yet). The Romantic period teaches us lessons that are applicable today because we are going through a similar technological revolution.

Words by Martin Lang | Senior Lecturer in Fine Art / Programme Leader, University of Lincoln

Footnotes

The spirit of the age: or, Contemporary portraits .. by William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt (1778 – 1830) Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Hazlitt: the original blogger by Dan Carrier via Islington Tribune

Critical Dilation: How William Hazlitt Judged Paintings by Paul Hamilton via Tate

Hazlitt on aesthetic democracy and artistic genius by Martin Lang