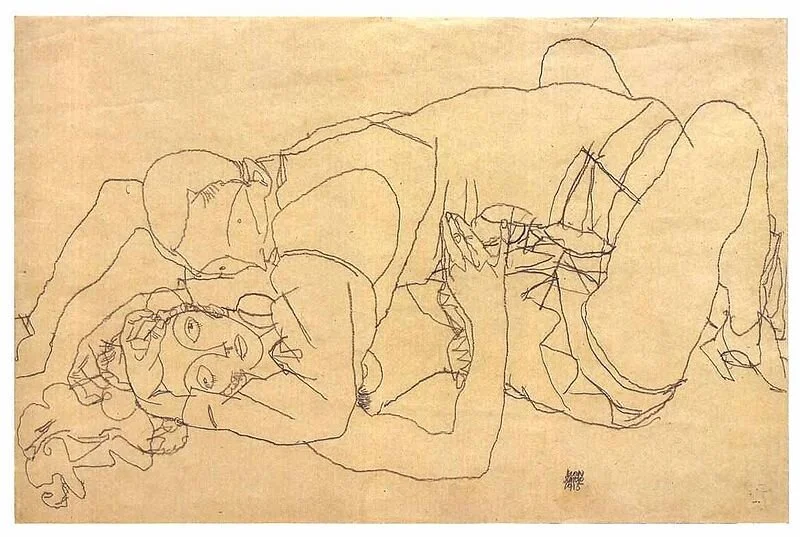

On the empty side of the bed

Illustration by © Egon Schiele

dying happily ever after death

Her finger wilts beneath the weight of her diamond rings. They sit on top of one another; their goldness intensified by the emptiness of her complexion. Maybe I notice them because she always seems to rest her hand against the soft part of her cheek, in the spot where Pa used to kiss her when he was still around.

‘Do you miss him?’ I ask her when we are alone. She pauses; looking at her lap as if checking for the answer. She returns a quiet gaze.

‘Everyday.’

I don’t stare at my grandmother’s rings because I have a fondness for vintage jewels. I stare because it makes me wonder what it would feel like to be left behind. What it would be like to roll into a cold spot between the sheets, a hollow space previously occupied—a quiet void in your own bed that doesn’t feel like yours. To become someone’s widow seems a lot less lovely than to be somebody’s wife.

Even so, nothing lasts forever, and wedding vows do warn that death will eventually do you part. I suppose no bride or groom ever thinks to ask about what happens next.

Can you actually live happily ever after (your lover’s) death?

Everybody’s story is different, but for some, the prognosis can be bleak. They call it the widowhood effect: the increased likelihood of someone dying shortly after they lose the one they love, sometimes within only a couple of hours, or a mere few days. The concept of being unable to live without someone has dominated art in all its forms since Romeo took his own life after losing Juliet. But far from being just a romantic—albeit morbid—notion, it’s now been proven that “I would die without you” is a legitimate sentiment.

Continue reading at The Haiku Times

Story originally published in issue three of JANE magazine.